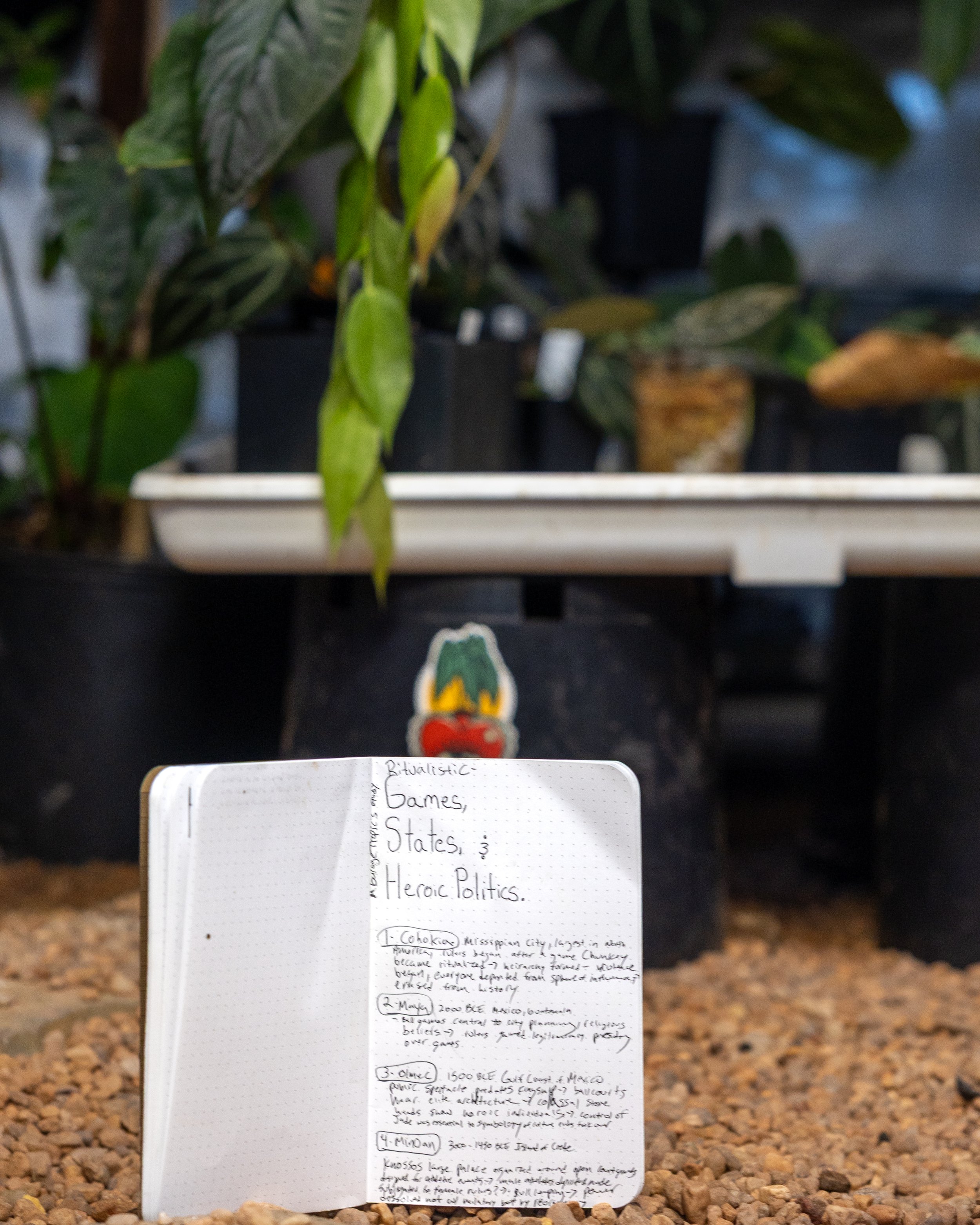

Games, States, and Heroic politics.

Samurai gradually became bureaucrats.

Spartan warrior-kings ruled through ritualized austerity.

Mayan priest-kings derived authority from calendars and games.

These are not anomalies. They are clues.

There are many historical examples of governmental apparatuses forming out of practices that were not originally “politics” at all. They began as games, festivals, seasonal roles, ritualized performances, or temporary leadership positions: tools for coordination rather than domination.

Many of us still operate under the assumption that human social evolution follows a simple arc: egalitarian hunter-gatherers → toolmakers → farmers → cities → massive populations → rulers → oppression. That story is tidy, intuitive, and largely wrong.

When the experts actually examine the archaeological and anthropological record, their finding make clear that hierarchy often emerged from imaginative coordination, not brute force. To organize and motivate groups larger than roughly 150 individuals, humans leaned on their most powerful adaptation: imagination. Through shared games, rituals, stories, calendars, and public spectacles, communities created cooperation at scale. From those cooperative labor pools came monumental architecture, infrastructure, and eventually sometimes… hierarchy.

Crucially, these hierarchies were often experimental, situational, and reversible.

Case Studies

1. Maya Civilization

Dates: c. 2000 BCE – 1500 CE

Region: Southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, western Honduras

Ballgames were staged in central plazas and embedded directly into city planning, making them civic events rather than marginal entertainment.

Early rulers appear first as hosts, referees, or interpreters of games—not distant monarchs issuing decrees. Authority emerged through visible participation and coordination.

Control of time: calendars, astronomy, and scheduling transformed repeated spectacle into lasting legitimacy, allowing elites to monopolize esoteric knowledge.

Archaeology suggests ballgames predate hardened dynastic states; over time, charismatic leadership crystallized into hereditary rule.

Notebook takeaway:

Game → calendar → dynasty

Public play created political gravity before permanent states existed.

2. Cahokia

Dates: c. 1050–1350 CE

Region: Mississippi River Valley, North America

Large public games such as chunkey synchronized vast populations across open plazas.

Authority appears to have been seasonal and situational at first—organizers, mediators, coordinators rather than permanent rulers.

Over time, elites monopolized cosmological alignment, mound space, and ritual authority.

When hierarchy hardened and exit remained possible, people dispersed. Cahokia was abandoned rather than conquered.

Notebook takeaway:

Coordination became control.

3. Olmec Civilization

Dates: c. 1500–400 BCE

Region: Gulf Coast of Mexico (modern Veracruz and Tabasco)

Large civic-ceremonial centers were organized around open plazas, indicating mass gatherings and spectacle before formal state bureaucracy.

Early ballcourts appear alongside elite architecture, embedding games directly within political space.

Colossal stone heads likely depict specific heroic individuals, emphasizing charisma and presence over abstract office.

Control of iconography, jade exchange, and symbolic systems allowed spectacle organizers to convert participation into lasting authority.

Notebook takeaway:

Heroic performance came before permanent political office.

4. Minoan Civilization

Dates: c. 3000–1450 BCE

Region: Island of Crete

Palatial centers such as Knossos were organized around large open courtyards designed for mass viewing of athletic and performative events, not throne rooms.

Bull-leaping and related spectacles emphasized skill, coordination, and risk, creating legitimacy through performance rather than coercion.

Elites translated repeated spectacle into administrative and economic control through trade networks, calendars, and symbolic knowledge.

When authority over-hardened or external pressures increased, palatial power collapsed and decentralized without total militarization.

Notebook takeaway:

Performance built power—and when performance failed, permanence vanished.

The Larger Pattern

The Roman strategy of “bread and games” is often cited as a way to distract populations from political agency. But these examples reveal something more subtle and more human.

Sometimes games are used to pacify populations.

Sometimes games create political authority.

Sometimes people accept that authority.

Sometimes they walk away.

The critical point is this: early hierarchies were not always born from violence or malice. They often emerged from play, imagination, and cooperation. Problems arose when temporary roles stopped rotating, when symbolic authority attempted to become permanent, and when exit was no longer possible.

Hierarchy was not destiny.

It was an experiment, and often, a failed one.