Interstellar nervy

I legit think they could’ve made Interstellar better if they had just swapped half the human survival drama for more physics and cosmology. The wormhole sequence alone could’ve been half the movie.

Homo sapiens showed up roughly 300,000 years ago. The observable universe is about 13.8 billion years old. And yet-somehow-we’re framed as the main attraction.

Let’s talk scale.

In that very old network of elemental particles, radiation, nuclear forces, dark matter, dark energy, spacetime; and you and me-there’s something physicists (not me, I’m just a Stan for Science) call the matter–energy budget. It’s the best accounting they have of what the universe is actually made of.

That accounting is tracked by what’s called the Concordance Model of Cosmology. As explained for laypeople like yours truly by Dr. Sabine Hossenfelder, it’s essentially a cosmic spreadsheet: where the stuff is, and how much of it exists.

According to NASA, the universe breaks down roughly like this:

69% dark energy

26% dark matter

5% ordinary (organic) matter

This first set of scales is the most trippy part for me because-well-we don’t know what 95% of the universe actually is. No confirmed interactions with dark matter have ever been detected (even with absurdly sensitive underground xenon detectors), and dark energy is understood only as the force driving the accelerated expansion of space itself.

That’s the baseline mystery.

Now let’s stack mass.

Black holes are massive.

That sounds obvious until you start stacking mass the way the universe actually does, without sentiment.

The Earth weighs about 6 × 10²⁴ kilograms. Mount Everest, all rock and ice included, comes in around 10¹⁵ kilograms; which sounds enormous until you realize Everest is basically a rounding error in Earth’s mass. An iPhone? About 200 grams. You could drop every iPhone ever made into the Sun and the Sun wouldn’t notice.

The Sun is where scale really starts to break the brain. It contains 99.86% of all the mass in the solar system. Every planet, moon, asteroid, and stray pebble combined? That’s the remaining 0.14%. The Sun weighs roughly 2 × 10³⁰ kilograms. If Earth were the size of a grape, the Sun would still be a beach ball, and mostly empty space. (the sun is not a big ball of gas, it has layers of varying density, with nuclear fusion creating pressure at the core keeping it from imploding)

But here’s where the humility lesson sharpens.

Our Sun is a fairly average star in a fairly average arm of the Milky Way, which contains somewhere between 100 and 400 billion stars. The galaxy’s mass isn’t dominated by stars at all, but by dark matter: a vast invisible halo outweighing everything luminous by about five to one. We don’t see it. We don’t touch it. We infer it because galaxies would otherwise fly apart.

Zoom out again.

Galaxies don’t float randomly. They trace filaments: enormous strands of matter stretching across hundreds of millions of light-years. These galactic webs look less like fireworks and more like fungal networks or neural tissue. Most of the universe’s matter isn’t even inside galaxies, but smeared thinly through these structures, quietly obeying gravity over incomprehensible timescales.

And sitting at the center of nearly every large galaxy-including ours-is something even more unbalanced.

A black hole with the mass of millions or billions of Suns, compressed into a region smaller than our solar system. Sagittarius A*, the black hole at the center of the Milky Way, weighs in at about four million solar masses. It doesn’t dominate the galaxy by brightness or size, but by gravity and bookkeeping. Nature has no problem concentrating absurd amounts of mass into places we barely understand.

If 69% of the universe is dark energy, 26% is dark matter, and only 5% is everything else: stars, planets, plants, people… then all of human history, every myth, war, cathedral, and iPhone keynote lives inside a thin cosmic residue. A statistical afterthought.

And yet; this is the quiet miracle, we’re part of the same accounting system. The same equations that describe black holes describe us. The same spacetime curvature that bends galaxies also bends the clocks in your phone.

The universe didn’t single us out as special.

But it did make us compatible with understanding it.

We’re not the main attraction.

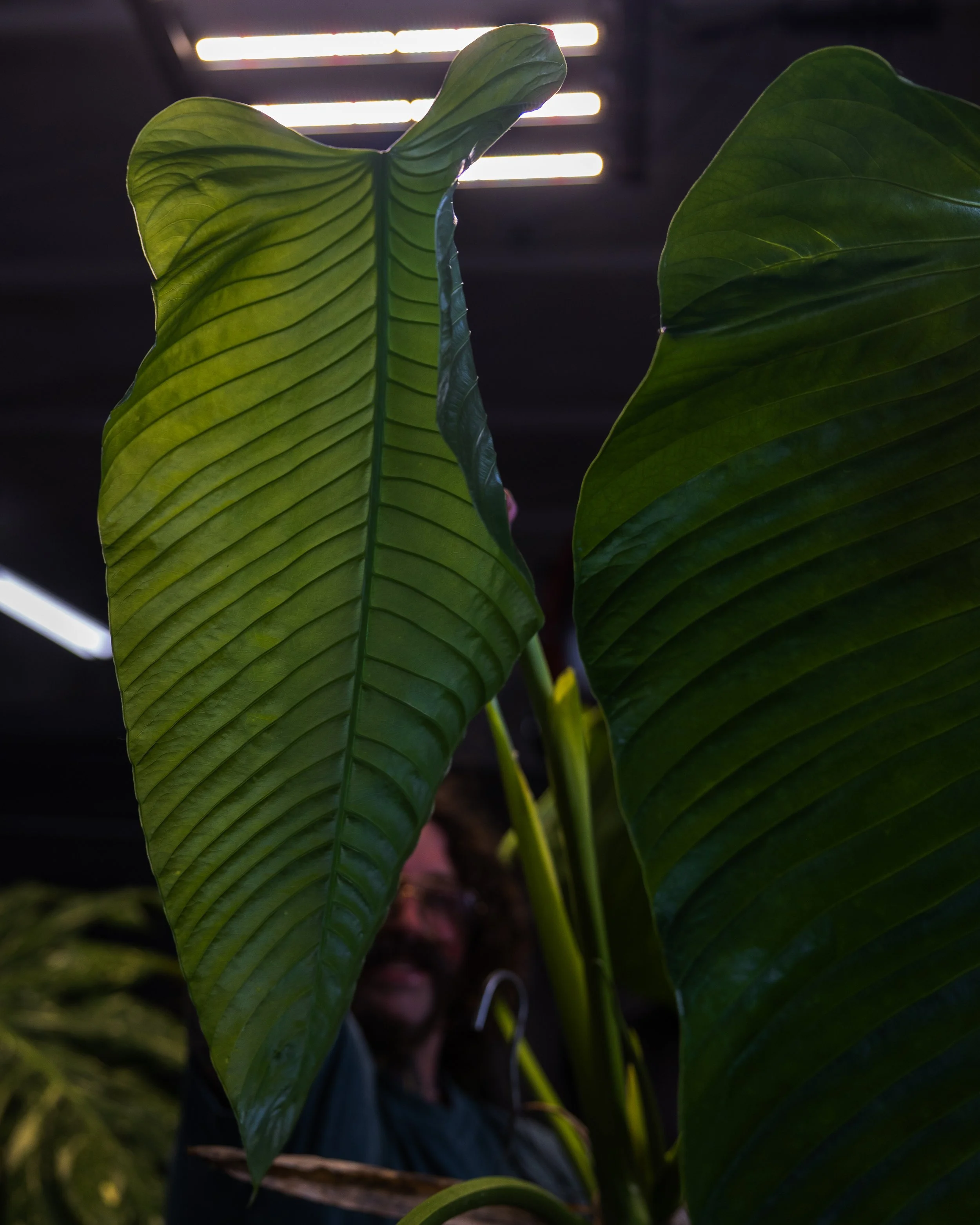

We’re a local pattern that learned to look up… I suggest looking up at giant leaves.

Black holes and giant leaves.

The plant: Anthurium nervatum

originally collected: Colce Panama, T. Croat

cloud forest

epiphyte

intense purple inflo

massive

care tips: have a lot of space, chunky mix, good water quality, can handle various lighting conditions, needs humidity above 50%, weekly feeding of balance fertlizers, likes being root bound.

Shocking plants in the rafters.

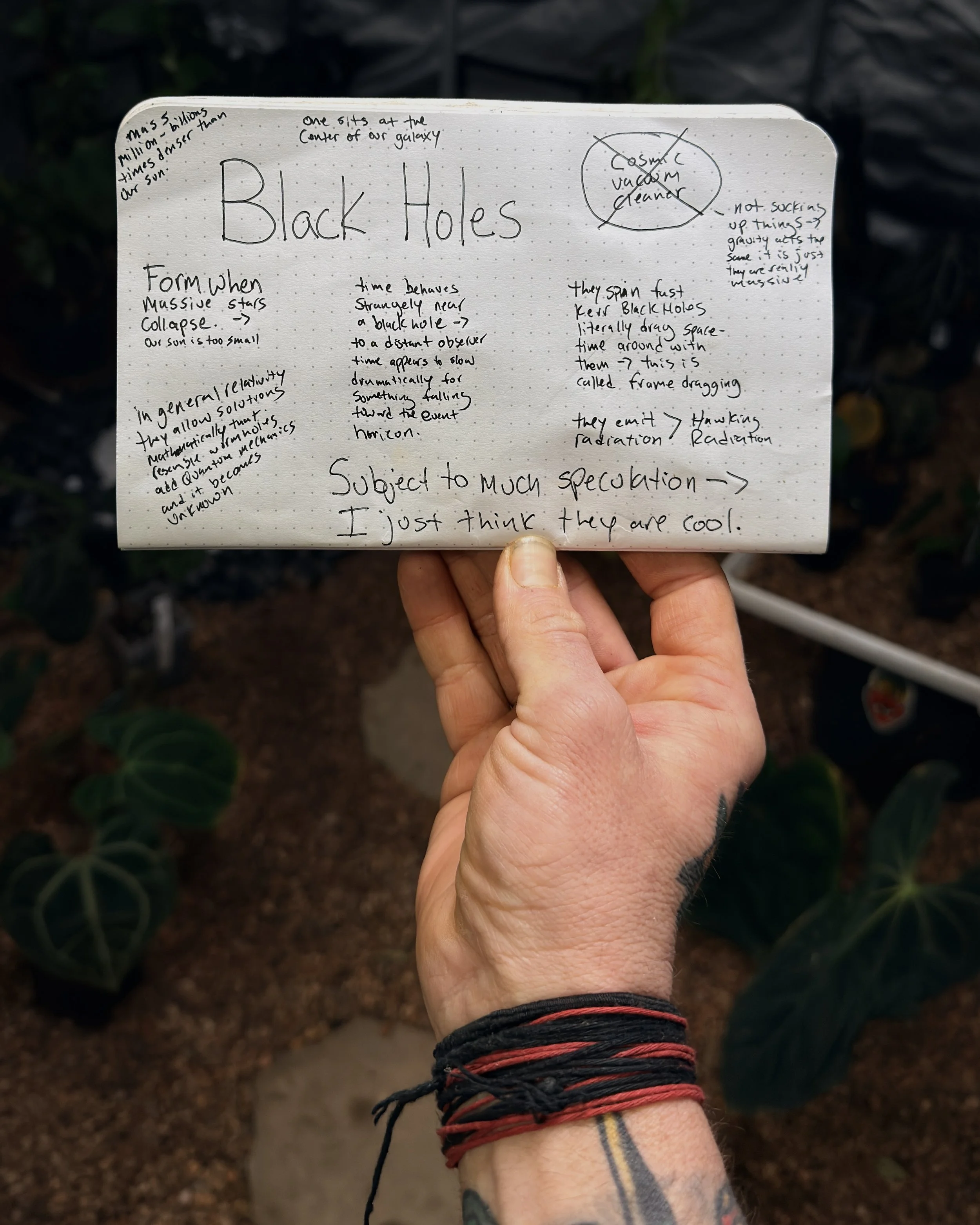

They aren’t cosmic vacuum cleaners.

A black hole’s gravity behaves like any other object of the same mass—get too close and you’re done, but it doesn’t “suck” everything nearby.The event horizon is the point of no return.

Once anything crosses this boundary, not even light can escape. From the outside, nothing beyond it can ever be observed.Time behaves strangely near a black hole.

To a distant observer, time appears to slow dramatically for something falling toward the event horizon (extreme gravitational time dilation).Black holes can spin—fast.

Rotating (Kerr) black holes drag spacetime around with them, a phenomenon called frame dragging.Supermassive black holes sit at galaxy centers.

Nearly every large galaxy—including the Milky Way—has one at its core, millions to billions of times the Sun’s mass.Black holes grow by eating and merging.

They gain mass by accreting gas, dust, stars, and by colliding with other black holes.They can power the brightest objects in the universe.

Quasars and active galactic nuclei shine intensely because infalling matter heats up before crossing the event horizon.Black holes emit radiation—very slowly.

Through Hawking radiation, black holes theoretically lose mass over immense timescales. Stellar black holes would take longer than the age of the universe to evaporate.We detect black holes indirectly.

By observing gravitational waves, orbital motion of nearby stars, X-ray emissions from accretion disks, and—recently—direct images of their shadows.

seed grown (F2) Anthurium nervatum ‘JV2 x HBG-RC’