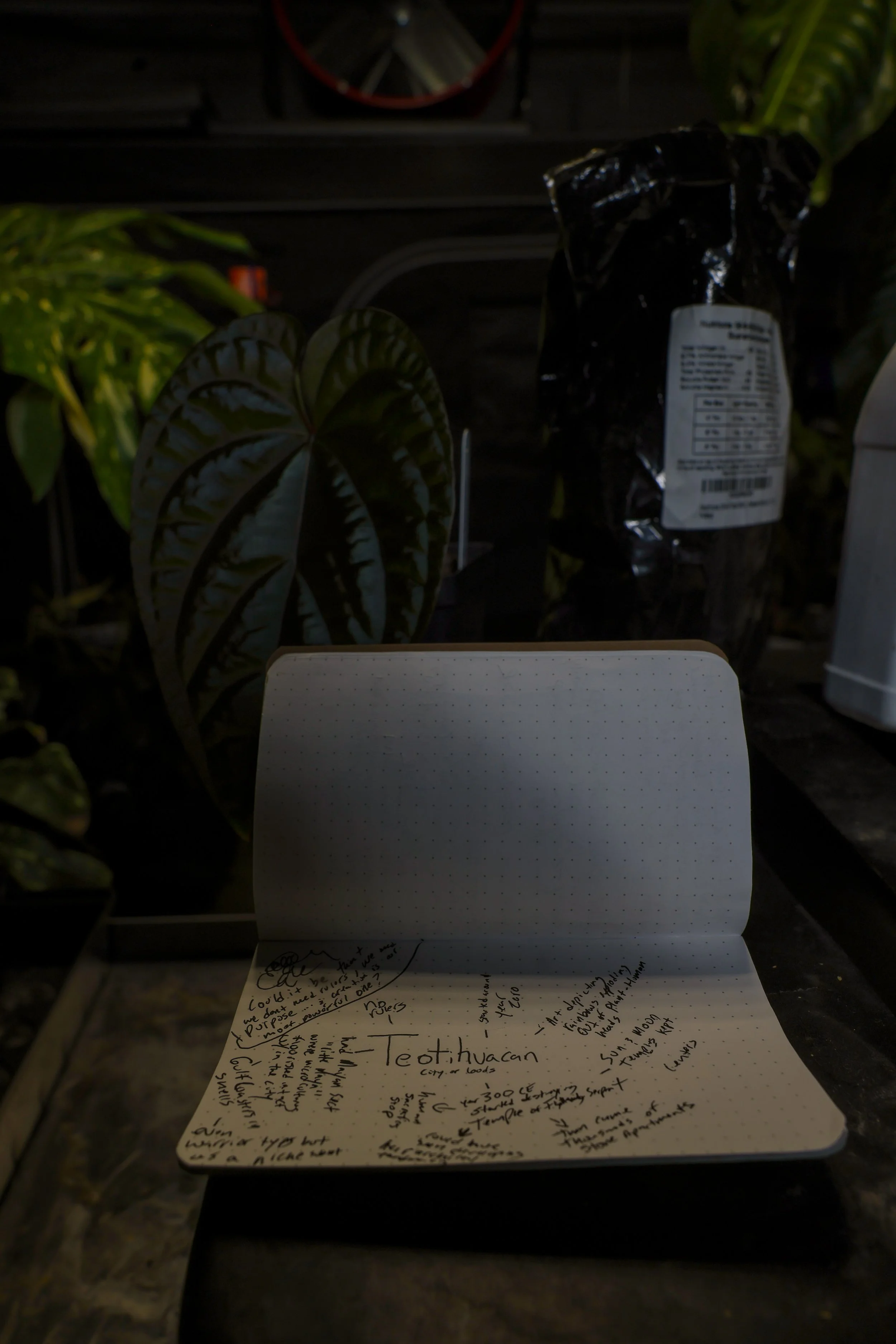

Destruction of the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, rainbow head explosions, and why a city of the gods in Mexico may prove humans just need something to work on.

The Carrot of the Gods

About thirty miles northeast of modern-day Mexico City sits Teotihuacan; once the sixth-largest city on Earth. At its height, around 300 A.D., it had broad avenues, apartment complexes, workshops, and pyramids that made Rome look provincial. And yet, the city left behind no known rulers, no dynastic records, not even a king’s name. Whoever ran Teotihuacan did it quietly; or collectively.

The art they left behind tells a stranger story. In murals from the old apartment compounds, bright plant-human figures sprout flowers from their bodies, rainbows and streams of liquid light bursting from their heads. These “flower people” weren’t praying to gods so much as becoming conduits of something cosmic-energy turning into life, life turning back into art.

For a long time, archaeologists assumed the city fell because it lost faith. The Temple of the Feathered Serpent, the one covered in stone serpents and shells; was burned, its sacrifices ended. But the city kept going. The pyramids of the Sun and the Moon were still in use, just stripped of their priests. Maybe they realized that endless ritual bloodletting was a dead end. Maybe they looked around and thought, Let’s do something different.

So they built. They organized. They laid out miles of perfect geometry in stone and obsidian, and raised apartment complexes that would’ve made modern zoning boards proud. It’s possible Teotihuacan replaced its gods with architecture. The sacred moved from the altar to the blueprint.

I can’t help but see the echo in us. We like to think we’ve evolved past all that mythic thinking, but we’ve only changed the offering. We don’t sacrifice hearts; we sacrifice hours. We worship productivity, consumption, and progress the way they once worshipped the rain. Capitalism is just the newest god that keeps us moving, building, wanting.

Maybe this is what the informational substrate; the deep logic that animates everything requires. It doesn’t need kings or priests; it just needs outlets. When people stop offering energy through ritual, they offer it through innovation. When that stalls, it re-routes through conflict. It’s the same circuit, just in different costumes. Rome had bread and circuses. Teotihuacan had pyramids and murals. We have streaming subscriptions and global logistics chains.

What the plant-humans on those walls were trying to say, I think, is that creation itself is the ritual. The rainbow explosions aren’t decoration; they’re instruction. Energy wants to move through us, one way or another. If we don’t build temples, we’ll build skyscrapers. If we don’t paint murals, we’ll build brands. Either way, the substrate gets what it wants; more pattern, more motion, more story.

So maybe Teotihuacan wasn’t a tragedy at all. Maybe it was one of humanity’s earliest experiments in rerouting devotion into design; a civilization that decided to turn worship into work. The art just reminds us that the current still runs through us. The question is whether we guide it; or let the carrot keep dangling forever.